H. T. Burleigh (1866-1949)

by Randye Jones

Henry (Harry) Thacker Burleigh was born on December 2, 1866, in Erie, Pennsylvania. His mother, Elizabeth, was a domestic worker because she was unable to get a teaching position despite her college education and fluency in French and Greek.

Henry (Harry) Thacker Burleigh was born on December 2, 1866, in Erie, Pennsylvania. His mother, Elizabeth, was a domestic worker because she was unable to get a teaching position despite her college education and fluency in French and Greek.

The people who musically influenced Burleigh’s life can be traced as far back as his maternal grandfather. Hamilton Waters was a partially blind ex-slave who worked as Erie’s town crier and lamplighter. As he performed his duties, he sang plantation songs to young Harry, thus passing on a music–the Negro spiritual–that his grandson would one day make known around the world.

Young Burleigh also heard several prominent performers who gave recitals at the home of his mother’s employer, Mrs. Elizabeth Russell. On one occasion, Burleigh

. . . heard that Rafael Joseffy was coming to give a concert there. He would hear it at any cost; so he stood in the snow up to his knees outside the window of the drawing-room of the Russell house. . . The lad was taken ill, pneumonia threatened, and in answer to his mother’s inquiries, he told of the hours in the deep snow. 1

Burleigh’s mother, who he credited as his strongest supporter, recognized his strong desire to hear music. She gained permission from Mrs. Russell to have Harry answer the door when guests arrived for concerts.

Into young adulthood, Burleigh took several jobs as a laborer to help support his family. Music, however, was his steady companion. He sang while at work, and he took advantage of any opportunity to hear musicians who came to town. He sang at school and in the choirs at St. Paul’s and Park Presbyterian churches and the Reform Jewish Temple.

After graduating from high school in 1887, Burleigh continued to improve his skills as a musician while he was employed as a stenographer for two area businesses.

In 1892, at the age of 26, Burleigh heard that the National Conservatory of Music was holding auditions for a scholarship. Burleigh journeyed to New York, departing Erie with only $30, which he had acquired through gifts and loans, and a letter of recommendation from Mrs. Russell. Burleigh biographer Jean Snyder described the experience:

The January 1892 reports in the Erie papers of Burleigh’s successful audition for the tuition scholarship gave no hint of the difficulty he experienced in the process. Burleigh gave the most detailed account in a 1924 interview. The audition for the tuition scholarship for the Artist’s Course stretched over four days. It required him to sing for the jury and demonstrate his ability in basic music skills such as sight-reading. Pianist Rafael Joseffy headed the audition jury. To be judged by the famous pianist whom he had heard from such an impossible social and artistic distance several years earlier would have daunted a singer with far more extensive professional experience. Burleigh was a veteran of many performances before Erie audiences, but this was the ultimate test–how would he measure against the rigorous artistic standards set for the National Conservatory?2

The adjudicators at his audition concluded that he fell just below the standards required to receive the scholarship. However, Frances MacDowell, the school’s registrar and an acquaintance of Mrs. Russell’s, intervened, and Burleigh eventually received a scholarship.

The subjects that Burleigh studied at the conservatory included voice with Christian Fritsch, harmony with Rubin Goldmark, and counterpoint with John White and Max Spicker. He also played in the orchestra and was its librarian. Because his scholarship only covered his tuition, he also had to work just to survive. In a description of his circumstances at the time, Burleigh stated that:

I used to stand hungry in front of one of Dennett’s downtown restaurants and watch the man in the window cook cakes. Then I would take a toothpick from my pocket, use it as if I had eaten, draw on my imagination and walk down the street singing to myself. That happened more than once or twice.”3

Among the contacts that Burleigh made during his years at the conservatory were composer Edward MacDowell, son of Burleigh’s benefactor, and composer/conductor Victor Herbert. However, it was his association with Czech composer Antonin Dvořák that most strongly influenced Burleigh’s career as a composer.

Dvořák came to the United States in 1892 as the new director of the conservatory. He learned of the spiritual through his contacts with Burleigh and later commented that:

. . . inspiration for truly national music might be derived from the Negro melodies or Indian chants. I was led to take this view partly by the fact that the so-called plantation songs are indeed the most striking and appealing melodies that have yet been found on this side of the water, but largely by the observation that this seems to be recognized, though often unconsciously, by most Americans. . . . The most potent as well as most beautiful among them, according to my estimation, are certain of the so-called plantation melodies and slave songs, all of which are distinguished by unusual and subtle harmonies, the like of which I have found in no other songs but those of old Scotland and Ireland.4

During Dvořák’s term as director, he encouraged other students to adopt his philosophy and used the melodies he heard Burleigh sing in his compositions. His major work of this period was his Symphony no. 9, “From the New World”, which was given its premiere in December 1893. He used portions of one of the spirituals, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” as a theme within the symphony’s first movement.

Burleigh spent many evenings singing the spirituals of his youth for Dvořák. He also did manuscript copying for the composer. In January 1894, Burleigh, along with soprano Sissieretta Jones, were the featured soloists in Dvořák’s arrangement of “Old Folks at Home,” presented in New York’s Madison Square Garden.

An event also occurred in 1894 that had a major impact on Burleigh’s life. He auditioned for the baritone soloist position at St. George’s Episcopal Church of New York. Although there was much debate about hiring a Negro to sing in the affluent parish, he was selected for the post over numerous other applicants. The beginning of this 52-year relationship marked the first time that Burleigh’s income allowed him to concentrate on his studies. He made several influential contacts, including entrepreneur J. Pierpont Morgan, who arranged additional engagements for Burleigh.

The next six years were very busy for Burleigh, both professionally and personally. In addition to his work as a singer, he completed his studies at the conservatory in 1896 and taught sight-singing there from 1895 until 1898. He married poet Louise Alston in 1898; their son, Alston, was born the following year. This was also the year that three of Burleigh’s early songs, on texts by his wife, were first published by G. Schirmer. In 1900, he became an editor for G. Ricordi, and he was selected as the first African-American to serve as soloist for Temple Emanu-El, an affluent New York synagogue.

Burleigh continued and expanded his contacts with the Black musical and academic community. He had two brief brushes with vaudeville. He was a guest lecturer and performer at Black colleges and universities. He became acquainted with celebrated personalities such as composers Will Marion Cook, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, and Robert Nathaniel Dett, and academicians Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois.

By 1916, Burleigh had published several works, mostly art songs. Most notable amongst these were “Jean” (1903), “Ethiopia Saluting the Colors” (1915), and song cycles Saracen Songs (1914) and Five Songs by Laurence Hope (1915).

He also wrote a few vocal and instrumental works based on the plantation melodies he had learned as a child. However, his 1916 setting of the spiritual, “Deep River,” is considered one of the earliest examples of concert spirituals–songs written in art song form specifically for performance by a trained singer.

Overmyer described the significance of Burleigh’s spiritual settings:

Burleigh’s work in preserving the slaves’ songs and making them known to the finest musicians, as well as to the public, is more important than is generally realized. Today we take for granted our possession of these musical gems. “Composed by no one in particular and by everyone in general,” and until after the Civil War never put down on paper, the Negro folk songs are part of the American heritage. Forty years ago, however, only a few of them were known in the North. Indeed, near the turn of the century, northern Negroes of some education had come to be almost ashamed of the credulous and illiterate old songs.5

Burleigh commented on his motivation for setting spirituals:

. . . In Negro spirituals my race has pure gold, and they should be taken as the Negro’s contribution to artistic possessions. In them we show a spiritual security as old as the ages. . . . These songs always denote a personal relationship. It is ‘my Saviour,’ ‘my sorrow,’ ‘my kingdom.’ The personal note is ever present. America’s only original and distinctive style of music is destined to be appreciated more and more.”6

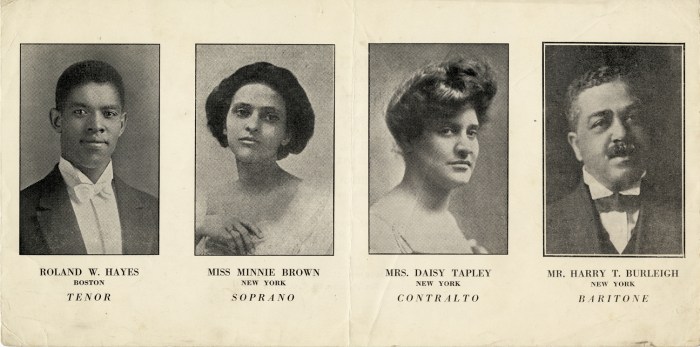

“Deep River,” and other spiritual settings became very popular to concert performers and recording artists, both black and white. It was soon normal for recitals to end with a group of spirituals. Musicians such as Roland Hayes, Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson made these songs a part of their repertoires.

There are various estimates of the number of songs Burleigh wrote. The numbers range from 200 to 300. They include settings used in musicologist Henry E. Krehbiel’s 1914 collection, Afro-American Folksongs, a Study in Racial and National Music, “By an’ By” (1917), “Go Down Moses” (1917), “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” (1917), and an Old Songs Hymnal in 1929.

The revenues from publication of Burleigh’s works helped pay for his extensive travels, including several trips to Europe, and his studies of languages. Over the years he performed for such dignitaries as the king and queen of England and President Theodore Roosevelt. He encouraged the careers of young musicians like Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, Carol Brice, Margaret Bonds, and William Grant Still.

Burleigh was a charter member of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) when it formed in 1914 and became a member of its board of directors in 1941. He received a number of honors, including the Spingarn Medal in 1917, and honorary degrees from Atlanta University and Howard University for his contributions as a vocalist and composer.

In 1944, members of St. George’s recognized his many years of service as soloist with gifts of $1,500 and a silver-banded cane. Later that year, he gave the fiftieth annual performance of Jean-Baptiste Faure’s “The Palms” at both morning and afternoon services, and he did a special performance of the work, broadcast over a local radio station, for New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia.

Illness forced Burleigh to retire as a soloist in 1946. His son, Alston, and daughter-in-law placed him in a Long Island rest home a few months later. Then, concerned about his father’s health care, Alston Burleigh moved his father to a nursing home in Stamford, Connecticut, in 1948.

On September 12, 1949, Harry Burleigh died of heart failure at the age of 82. His funeral was held at St. George’s and was attended by 2,000 mourners. Some of his choral and solo settings were sung during the service, and the pall bearers included composers Hall Johnson, Noble Sissle, Eubie Blake, William C. Handy, and Cameron White.

In its September 16, 1949, obituary, the Vineyard Gazette of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts–where Burleigh had vacationed for a number of years–said of the composer:

In its September 16, 1949, obituary, the Vineyard Gazette of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts–where Burleigh had vacationed for a number of years–said of the composer:

In 1927 a Gazette interviewer found him at the Shearer cottage on the Vineyard Highlands at Oak Bluffs where even then he had been summering for more than ten years. His bedroom was also a studio, its windows looking out upon tangled green countryside. In these surroundings he did much of his work of arrangement and composing, although he came to the Island for rest. “The only difficult thing about interviewing this singer and composer with the worldwide reputation,” the Gazette reporter wrote, “is that he is constantly veering away from the subject of his own work to praise that of others.”7

Simpson commented that:

The “dapper little man with the white mustache” had indeed laid down his burden. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, Hastings-on-Hudson in White Plains, New York. . . . A few weeks later another tribute was paid Burleigh in the St. George’s Bulletin, October 2, which read in part: “He seemed aware of deeper tones of brotherhood and throbbing harmonies of humanity which others did not hear.” 8

__________________

1 Anne Key Simpson, Hard Trials: the Life and Music of Harry T. Burleigh (Metuchen, N.J.: The Scarecrow Press, 1990), 153.

2 Jean E. Snyder, “Burleigh at the National Conservatory of Music: ‘In the Center of American Musical Activity.'” In Harry T. Burleigh: From the Spiritual to the Harlem Renaissance, University of Illinois Press, 2016, 65-74. Accessed February 19, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt18j8x96.9.

3 A. Walter Kramer, “H.T. Burleigh: Composer by Divine Right and ‘The American Coleridge-Taylor,'” Musical America, 29 April 1916, 25.

4 Lester A. Walton, “Harry T. Burleigh Honored To-day at St. George’s,” The Black Perspective in Music 2 (Spring 1984): 81. (Reprinted from the clippings file at the Schomberg Library (New York), March 30, 1924).

5 Antonin Dvořák, “Music in America,” Harper’s 90 (1895): 432.

6 Grace Overmyer, Famous American Composers (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1945), 135.

7 “H. T. Burleigh Was One of Music’s Great Figures,” The Vineyard Gazette Time Machine. Accessed February 9, 2024. https://vineyardgazette.com/news/1949/09/16/h-t-burleigh-was-one-musics-great-figures

8 Walton, 83.

The Spirituals Database is a searchable listing of compact discs, long-playing discs, 78 rpm, and audio cassette recordings by various vocalists, including this artist, of Negro Spirituals set for concert performance. Information is available about song selections spanning a century from Burleigh’s “Deep River” to the present day. To see the recordings by this artist currently represented in the database, please click on the image to the right.

The Spirituals Database is a searchable listing of compact discs, long-playing discs, 78 rpm, and audio cassette recordings by various vocalists, including this artist, of Negro Spirituals set for concert performance. Information is available about song selections spanning a century from Burleigh’s “Deep River” to the present day. To see the recordings by this artist currently represented in the database, please click on the image to the right.

Afrocentric Voices in Classical Music. Created by Randye Jones. Created/Last modified: February 9, 2024. Accessed:. http://www.afrovoices.com/wp/harry-thacker-burleigh-biography.